- Published on

Multi-task Self-Supervised Visual Learning (Aug 2017)

- Authors

- Name

- Yann Le Guilly

- @yannlg_

The paper can be found here: https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.07860

0. Introduction

This work focuses on Computer Vision. Unlabeled images and videos are nowadays easily available and deep learning models are, despite being state-of-the-art for common tasks (image classification, segmentation, object detection, etc) known to data staved. Therefore, it is natural to try to leverage those data to train our models. However, unsupervised learning methods are not yet as efficient as supervised algorithms. And labeling data is in many cases a big issue.

Self-supervised learning is an attempt to combine the good points of both unsupervised supervised methods. Indeed, it removes the burden of labeling data (but still uses automatically labeled data, therefore self-supervised) and uses easy-to-measure tasks (like predicting the next step(s) of a time series).

The contribution of this paper is triple:

- Implement 4 self-supervision tasks (relative position, colorization, "exemplar" task, and motion segmentation)

- Evaluate the performance of the combined tasks

- Discuss potential issues from combining naively those tasks

1. Multi-task Self-Supervised Visual Learning (SSL)

1.1. Self-Supervised Tasks

The authors selected 4 tasks among many others that were brought by other papers. Those selected tasks are chosen because of their simple concept and as diverse as possible.

Relative Position[1]

A grid is applied to an image. 2 adjacent patches are extracted and fed into a model that has to predict the relative position of a patch to the other. The network output is an eight (up, down, left, right, left-up, right-up, left-down, right-down) categories softmax classification. In order for the model to not learn the colors, the authors randomly drop 2 of the 3 color channels and replace them with noise.

Colorization[2]

From a grayscale image, the network has to predict the color of the original pixels. The implementation is described in [2].

Exemplar[3]

Here the network has to discriminate 2 patches from the same image and and the same from another image . As [5], the authors use a triplet loss defined as:

With the (cosine) similarity between 2 patches. is a margin set to .

Motion Segmentation[4]

In the video, from a given frame, the network has to predict which pixels will move in the next frame. The implementation follows [4] except for the tracking algorithm where [6] is used.

1.2. Naive Architecture

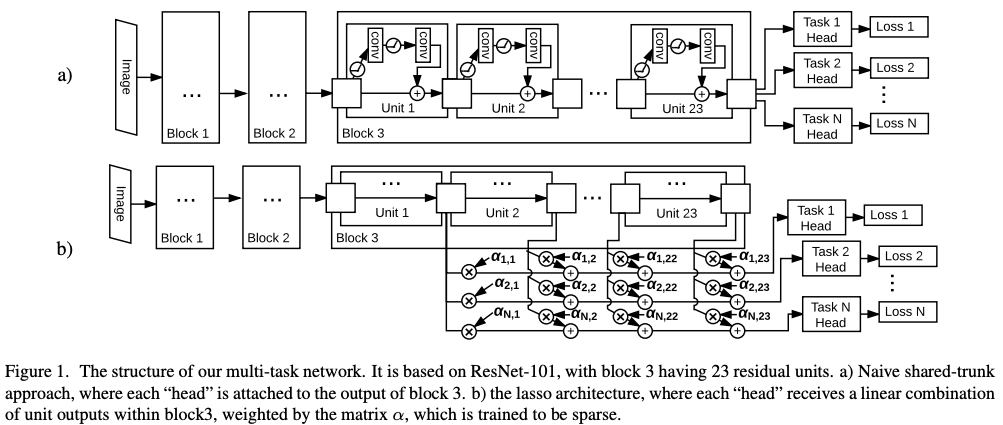

All architecture starts with a ResNet-101 v2 [7]. Block 4 of ResNet-101 is removed in order to save computation. Each task is computed in a "head" and the heads are directly coming after block 3.

1.3. Lasso Separated Features Architecture

Unlike the first architecture, here the assumption is that different tasks require different features. Therefore, in this architecture, the output of the layers is allowed to be skipped by using an L1 penalty. This encourages the combination of layers to be sparse and therefore the network to concentrate all the information required by a single task into a small number of layers.

2. Experiments

The models are tested on 3 evaluation tasks:

- Image classification on ImageNet

- Object detection on PASCAL VOC 2007

- Depth prediction on NYU V2

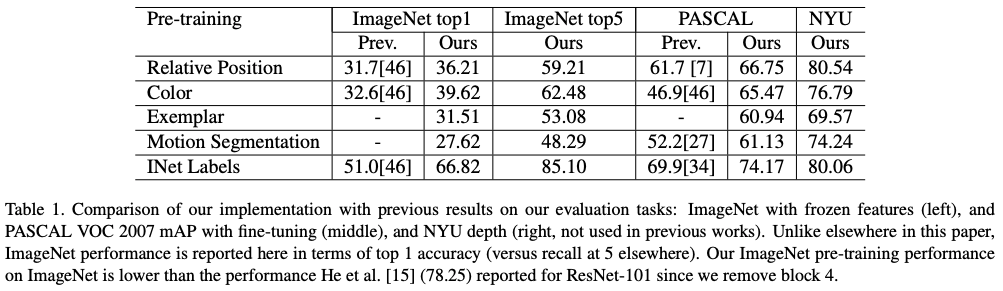

For object detection, the authors use Faster-RCNN [8] and [9] for depth prediction. In all tasks, the based model is pre-trained with the self-supervised tasks. Then in the evaluation, the weights are frozen and the authors are using a single linear classification layer for ImageNet or integrated as the backbone (still frozen) for object detection and depth prediction. The reported results are top-5 accuracy. Except in table 1 where it is top-1.

2.1. Comparison of Self-Supervised Tasks

First, the self-supervised tasks are compared to each other. The results are given in Table 1. The authors' implementations are already slightly better due to better data augmentation and longer training.

Overall we can notice that self-supervised tasks alone are all underperforming compared to regular supervised learning.

2.2. Comparison with the Naive Architecture

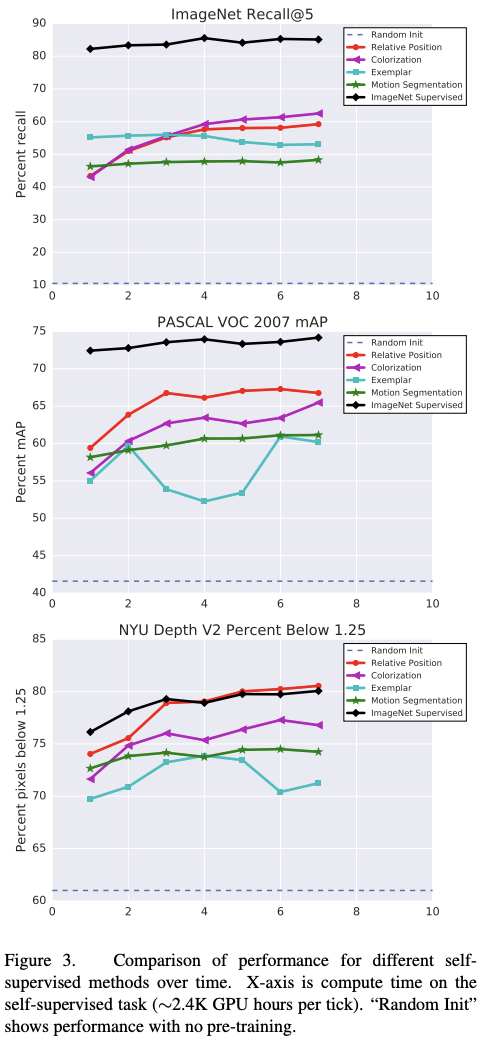

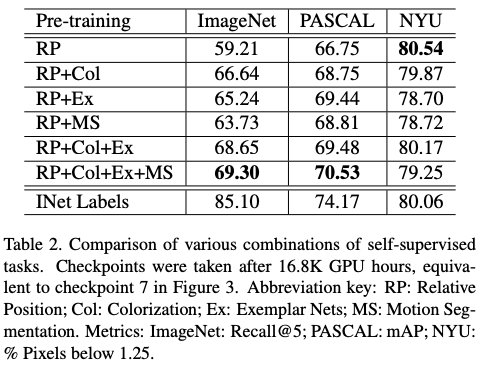

Table 2 shows the results for combining self-supervised pre-training tasks.

The pre-training appears to be the most efficient for PASCAL VOC with "only" ~4% under the pre-training on ImageNet. On the depth prediction task (NYU), only Relative Positioning seems enough to reach (and slightly over) the performance of the baseline.

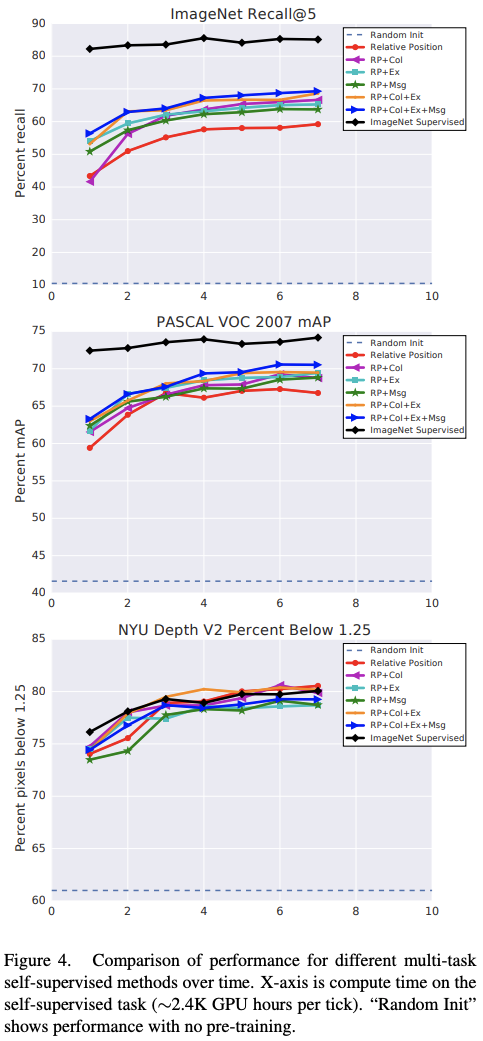

The figure 4 shows the effect of training time.

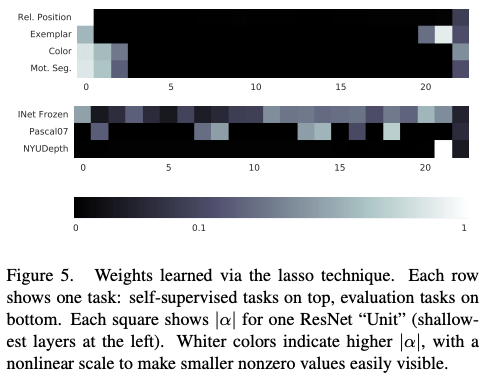

2.3. Comparison with the Lasso Architecture

Figure 5 suggests that the final output space for the representation is still losing some information that’s useful for evaluation tasks.

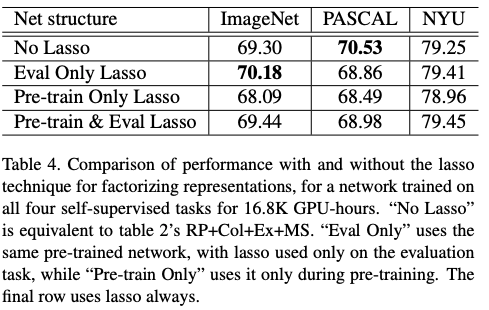

All the results are compiled in table 4. Using lasso performs slightly better than without. Also, it is interesting to notice that using the regularization in the evaluation task only performs better than for both pre-training and evaluation.

3. Conclusion

The authors list their findings in 5 points:

- The depth of the network improves self-supervision over shallow networks

- Combining self-supervision tasks improves the performance

- On the tested architecture, the classification accuracy is far from the regular method, closed for PASCAL VOC and same for depth prediction on NYU

- Harmonization (detailed in the paper) and lasso weightings only have minimal effects

- Combining self-supervised tasks leads to faster training

References

- Carl Doersch, Abhinav Gupta, Alexei A. Efros: Unsupervised Visual Representation Learning by Context Prediction. In ICCV, 2015 (arxiv.org/abs/1505.05192).

- R. Zhang, P. Isola, and A. A. Efros. Colorful image colorization. In ECCV, 2016 (arxiv.org/abs/1603.08511).

- A. Dosovitskiy, J. T. Springenberg, M. Riedmiller, and T. Brox. Discriminative unsupervised feature learning with convolutional neural networks. In NIPS, 2014 (arxiv.org/abs/1406.6909).

- D. Pathak, R. Girshick, P. Dollar, T. Darrell, and B. Hari- ´ haran. Learning features by watching objects move. arxiv.org/abs/1612.06370, 2016.

- X. Wang and A. Gupta. Unsupervised learning of visual representations using videos. In ICCV, 2015 (arxiv.org/abs/1505.00687).

- H. Wang and C. Schmid. Action recognition with improved trajectories. In ICCV, 2013 (hal.inria.fr/hal-00873267v2).

- K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun. Identity mappings in deep residual networks. In ECCV, 2016 (arxiv.org/abs/1603.05027).

- S. Ren, K. He, R. Girshick, J. Sun. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. In NIPS, 2015 (arxiv.org/abs/1506.01497).

- I. Laina, C. Rupprecht, V. Belagiannis, F. Tombari, and N. Navab. Deeper depth prediction with fully convolutional residual networks. In 3D Vision, 2016 (arxiv.org/abs/1606.00373).